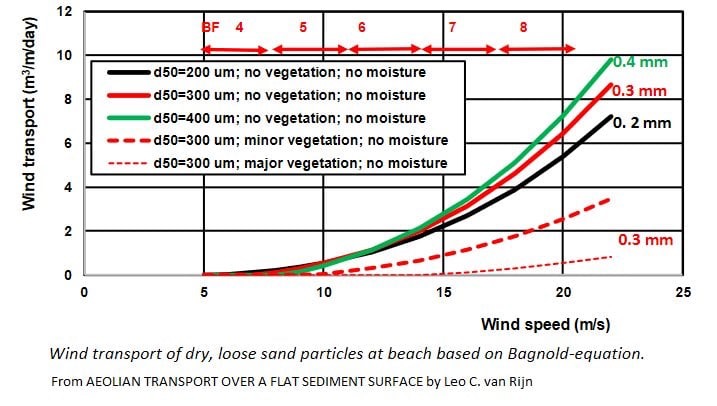

Offshore sandbanks are never static, their substrate is moved around by tides, and when they are exposed and have time to dry out, by the wind too. Sometimes these forces align to produce very rapid (in geological terms, though sometimes also in human terms) movements. These can be enough to smother coastal towns completely.

Nearby examples of towns damaged or destroyed by moving sand banks:

Meols: In the late 15th Century, Meols was continuously inhabited from prehistoric times until the close of the 15th Century. Whilst there are no contemporary descriptions of events that led to the abandonment, there is a thick layer of wind-blown sand that covered habitations and agricultural lands alike. The seat of the de Melas family was relocated to Wallasey due to degradation of the fields and loss of the Manor House. It is believed that an extreme weather event caused an offshore sandbank to move inland with such suddenness that there was little time to retrieve possessions. Consequently, Meols is renowned as one of the richest medieval archeological sites in the country (1,2) Wirral’s own sandy Pompeii!

There are other less well-described incidents in the medieval period, including Birkdale, Ainsdale, Formby, Crosby, and Hightown (2)

Formby: In 1739, Formby suffered a second catastrophic sand inundation which was described in contemporary literature:

“In 1690 there was a deep-water channel close to the shore at Formby, with a sandbank outside it which gradually came nearer and nearer. At length, it joined the coast, from which sand commenced to blow, so that in a short time the cultivated ground, gardens, orchards and streets of Formby were entirely covered up.” (3)

This necessitated the brick by brick removal, relocation and reconsecration of the Church. Formby was saved from further inundation by the labours of Mr Freshfield who created and planted sandbanks as a barrier to further wind-blown sand, and eventually, the ground lost to sand was reclaimed.

St Annes 1918-1938: The North Channel of Ribble ran around 200m from the promenade at St Anne. In the late 1800s, the channel started to fill with silt following reduced water flows. By 1910, the channel was no longer navigable and by 1918 it was just a muddy gutter. This gutter filled with wind-blown sand from the Horse Bank, which formed an unbroken sand transport pathway directly to the promenade. By 1930 the beach level at St Annes had risen by 7m. Sand regularly blew over the road, cutting off access and the promenade was unusable. The town council tried to hold back the sand with a sand shield, but this failed after a few years. Costs of clearing up mounted and eventually a decision was made to learn from the fate of Formby. Starr Grass was profusely planted to stabilise the sand collecting against the promenade wall into fixed dunes 4,5

The situation at Hoylake in 2021 is more or less identical to those at Formby in 1720 and At Annes in 1920. We have lost a channel (the Hoyle Lake,) even its silt is now covered in sand and a large sandbank (the East Hoyle) is moving ashore.

References

1 Brown, P. J. (2015). Adverse weather conditions in medieval Britain: An archaeological assessment of the

impact of meteorological hazards, Masters Thesis, University of Durham (LINK BROKEN)

University School of Archaeology: Monograph 68, Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford

3. De Rance, C. E. (1877). The superficial geology of the country adjoining the coasts of southwest

Lancashire, comprised in sheet 90, quarter-sheet 91SW, parts of 89NW and SW, 79NE and 91SE of the 1-inch geological survey of England and Wales.Memoirs of the Geological Survey of England and Wales. Longmans, London