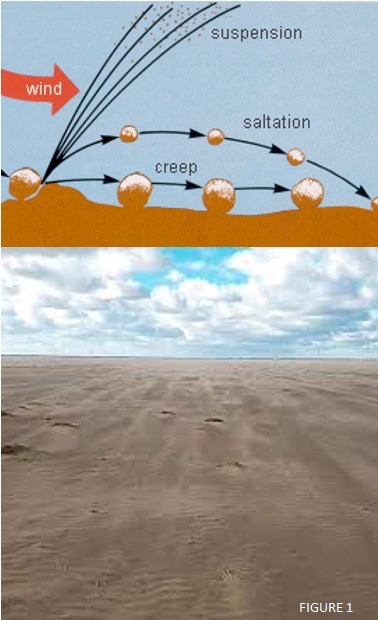

How wind moves sand

At Hoylake, most windblown sand is moved by three main methods which depend on the wind speed and especially the size of the sand grains.

At Hoylake, >95% of sand moves by saltation a sort of hopping action – when a sand grain “hops” and when it lands dislodges more grains and they dislodge more, until a cascade of sand starts moving in the wind a few cm above the beach – see Figure 1

Saltation can start with wind speeds as low as 5m/s (11mph) but if the beach is wet, after a tide or rain, it takes stronger winds to start the sand moving.

If the prevailing winds blow over a large expanse of sand, there is more chance of it drying out and the conditions for saltation to occur.

Once in motion, the saltating sand will continue moving until:

- The sand particles are in the lee of a raised object

- The wind drops

- The sand particles meet an uphill gradient that is too steep for the wind

- The sand particles hit a wet patch or an area bound with silt or a salt crust

Increasing average winds, a greater expanse of sand or less frequent coverage by the tide will increase the amount of sand delivered to the promenade.

Why there is a greater risk of sand blowing onto the promenade

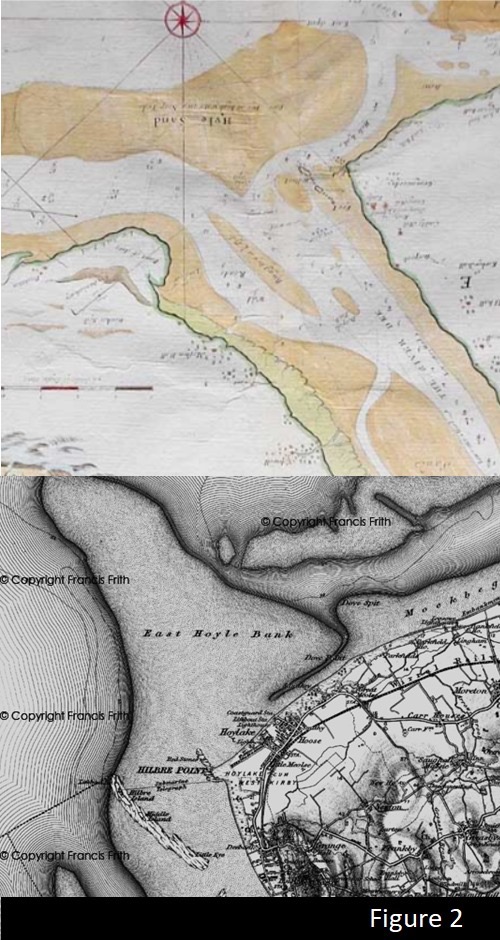

- In the 1660s when the 1st map in figure 2 was created, the Hoylake lake was less of a lake and more of a channel, 5m deep at the Hilbre end and 10m deep at the Dovepoint end.

- It was used as a sheltered [by the East Hoyle bank] deep-water anchorage

- Kings Gap, was a small and managed gap in the huge dune system on N Wirral that allowed convenient access to horse-drawn traffic.

- Tidal forces have redistributed the sands of the E.Hoyle since the last Ice Age, gradually filling in the Hoyle “lake” The second map is from an 1899 survey and shows that the channel was now a gutter reaching about ½ the original length

- As recently as 10 years ago the mud and silt of the Hoyle Lake was easy to encounter just by walking seawards, though the permanent gutter had gone.

- Before about 1850, there was only around 70-700m of exposed sand that could saltate offshore, but that was enough to build dunes. Figure 3

- Even when the “Lake” filled the wet sand and mud of the remnant gutter protected the promenade from the bulk of sand blow in from the East Hoyle bank because it broke the sand transport pathway for saltation.

- Now there is no protection from the vast expanse of the East Hoyle bank’s wind-blown sand and a direct sand transport pathway has developed

- Mean High water mark is retreating at up to 75m/decade, so more of the bank is dry more often

- Climate change makes extreme weather events more likely.

Consequently, we can expect a lot more sand to be delivered a lot more frequently.